- Home

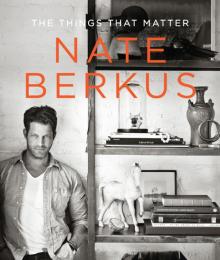

- Nate Berkus

The Things That Matter

The Things That Matter Read online

Copyright © 2012 by Nate Berkus

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Spiegel & Grau, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

SPIEGEL & GRAU and Design is a registered trademark of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Berkus, Nate

The things that matter / Nate Berkus.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-679-64432-3

1. Berkus, Nate—Themes, motives. 2. Interior decoration—Psychological aspects. I. Title.

NK2004.3B47 A4 2012

747.092—dc23 2012032445

www.spiegelandgrau.com

Photography by Roger Davies

Additional photography by Rainer Hosch and Kevin Trageser

Book design by Gabriele Wilson Design

v3.1

TO F.

(Illustration Credit col3.1)

I’ve always believed your home should tell your story. That pine table over there? I found it in a shop just outside of Mexico City. The sun was beating down and I was a little hungry, but I saw it and I knew I wanted to look at it every day. Those cuff links? They belonged to somebody I loved; we picked them out on one of the most perfect days we ever spent together. That tortoise shell on the wall? There was one exactly like it in my mother’s house and I can’t see it without thinking about a thousand inedible family dinners. Each object tells a story and each story connects us to one another and to the world. The truth is, things matter. They have to. They’re what we live with and touch each and every day. They represent what we’ve seen, who we’ve loved, and where we hope to go next. They remind us of the good times and the rough patches, and everything in between that’s made us who we are.

—NATE

(Illustration Credit col5.1)

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

TO BEGIN WITH

TO BEGIN AGAIN

BRIAN SAWYER

BARRI LEINER GRANT

KELLY FRAMEL

STEVE BERG

CHRIS GARDNER

DR. RUTH WESTHEIMER

BARBARA HILL

DOLORES ROBINSON

CORIN NELSON

FABIOLA BERACASA

SANDY FOSTER

BROOKE & MICHAEL HAINEY

NATE BERKUS

THINGS THAT MATTER TO…

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

About the Author

About the Photographer

(Illustration Credit col6.1)

(Illustration Credit col8.1)

(Illustration Credit 1.1)

Over the years I’ve read lots of stories about people who knew exactly who and what they were going to be by the time they were done teething. In fact, I envy anybody who can make their way through childhood and adolescence with that level of confidence. In any case, it did become clear early on that I was a creative person, but when you’re a kid growing up in suburban Minneapolis, it’s hard to imagine that you’ll be starting your own design firm at the age of 22, let alone joining the Oprah Winfrey team, flying all over the country doing makeovers, writing books, producing films, hosting your own TV show, and developing a home design collection that’s accessible to everyone. I don’t know where you were in junior high, but I was way too busy praying for clear skin and debating whether Madonna was really better than Cyndi Lauper to worry about the big picture.

I did know I felt out of place, and restless, and adventurous in a way that some of my friends did not, and I knew there were things I wanted to see and do and experience in my life that most of the people around me could take or leave. I always sort of sensed there was a wider world out there—something beyond just taking the bus to and from Hebrew school.

My mother in the lap of my grandmother: two generations of great style (Illustration Credit 1.2)

I may have resisted acknowledging it throughout my teenage years, but I now understand that the joy I take in transforming interiors comes from my mom, an interior designer, who has always been about creating a beautiful home. Rooms in our house were in perpetual motion. Fabric samples were laid out everywhere. Overnight a storeroom would become a spare bedroom; a spare bedroom, a TV watching den; a den, a spot for wrapping presents. If my mother wanted to hang a huge canvas in the living room, but couldn’t find a painting she could afford, or one she loved enough, she would just paint something herself.

My mother had, and has to this day, an unbelievable sense of scale. She’s an artist who is amazingly skilled at laying out a space. Not only are her rooms comfortable; they make perfect sense. Thanks to her, my earliest memories center around design, collecting, and figuring out where everything should go. While other kids were studying algebra, I was studying my mom’s collection of tortoise glass. Instead of watching The Love Boat, I was watching as she pounded hooks into the living room wall, or helping to stuff a newly reupholstered chair into the trunk of her car.

But it wasn’t only my mother. For my dad, an entrepreneur and businessman, everything had to be the best, the finest, the top of the line. His shirts and suits back in the 1980s were all custom-made and immaculately tailored. His shoes were Italian, his cars were hot. As a founder of the National Sports Collectors Convention, he was able to bring his business sense in line with his collector’s mentality, a nostalgist’s love for old, high-quality things. I remember him saying to me, “You have to dress well in this world, because everyone notices what you’re wearing and they make a decision about you immediately. And anything you say after that, well, if they’re smart, people will listen, even if they’ve already sized you up—but Nate, most people are not that smart.”

With parents like these, it was hard not to absorb a love of design, harmony, precision, quality, and beauty. Their lessons lasted—their marriage did not.

My parents split up when I was 2 years old. We were living in Los Angeles at the time, and after the divorce, my mother and I returned to Minnesota, where her parents lived, and where she eventually met and married my stepfather. Throughout my childhood, I would fly back to California to visit my dad. I was what the airlines called an “unaccompanied minor.” Over time I developed such precocious assurance that when the flight crew told me they could release me only to a parent or guardian, I would answer with all the breeziness of a 6-year-old kid, “It’s okay, my father is meeting me downstairs. I know what to do.” And then I’d go down the escalator, find my suitcase on the carousel, head outside the terminal, flag down my dad (or the driver he’d sometimes send), and that was all there was to it. Today, when I tell this to friends with young children, their jaws drop and they all say how fortunate I am that my face never graced the side of a milk carton. But hopping on a plane to see my father was the only thing I’d ever really known and it felt perfectly natural to me. I was a capable kid and I think the experience taught me to navigate the world with a degree of independence and flexibility and fearlessness that still serves me well.

Mom and Dad, California, 1970 (Illustration Credit 1.3)

Back home in Minnesota, though, I was a boy with one dream and one dream only: I wanted—no, strike that, I was desperate for—a room of my own. You see, in those days I shared a room with my little brother, Jesse, and it wasn’t pretty. He was the Oscar to my Felix: messy, careless, and just a little bit sticky—exactly the way a kindergartner is supposed to be. I, on the other hand, was a triple Virgo: frighteningly organized and utterly meticulous—exactly the way a controlling 5th-grade neat freak is supposed to be. I wanted the laundry stacked, sorted, and put away the second it came out of

the dryer, whereas my brother lived happily with stuff tossed all over the place. The only LEGO-free zone I was able to maintain was my bed, and believe me, I made it flawlessly. Even as a 10-year-old, I remember trying to explain to my mother and stepfather how upset and frustrated a messy room made me. But they just couldn’t grasp it. They wanted me to be playing with baseballs and frogs while I wanted to be scouring garage sales.

Mom and me, Minneapolis Airport on the way to boarding school (Illustration Credit 1.4)

I don’t know if my mother simply got fed up with refereeing the epic battles between Jesse and me or if it was starting to dawn on her that I just wasn’t a baseball-and-frog kind of guy, which is what I’d told her when she signed me up for T-ball. Actually, I believe the exact quote was, “I don’t like direct sunlight, I don’t like the feeling of grass under my feet, and I don’t like mosquitos, so I don’t know why you think I’m going to enjoy a summer of this!” But my parents more than made up for it in the fall, giving me the greatest present I could’ve ever imagined for my 13th birthday. Forget the savings bonds, fountain pens, and Kiddush cup that most Bar Mitzvah boys receive, my mother and stepfather announced that they would be allowing me to renovate an unfinished section of the basement—concrete floors and no drywall—and turn it into my own bedroom.

Moving into a space that I could call mine and, even better, watching it gradually take shape was a major turning point for me. I was involved in every single design decision. The rest of our house may have been done in French Country, but my bedroom was going to be grays, blacks, and reds—a subterranean oasis of the urban ’80s in the dead-center of suburban Minnesota. During class, I sat staring at the clock, waiting for the afternoon bell to ring. Most kids race home to play video games or kick a soccer ball; I ran all the way from the bus stop to see if my countertops had come in, or if the guys had installed the bathroom sink yet. In a matter of months, my bedroom had gray carpet with darker gray pin dots, built-in oak furniture with satin-nickel pulls, gray laminate countertops, pale gray grass-cloth wall covering, and a gray laminate bed with red-and-white bedding. The bathroom was white tile, with gray countertops and oak cabinets with a clear stain. You know, just your basic 13-year-old kid’s space circa 1984.

Jesse, Marni, and me

Dan, Steve, and Bob (Illustration Credit 1.6)

Without having this design laboratory of my own, I seriously doubt I would ever have had the confidence so many years later to make sweeping design decisions (let alone have other people foot the bill for them). Over the next few years, I must have rearranged that room a thousand times. Some kids spent their allowance going to see Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom; I spent mine on a great-looking lamp I’d found at the flea market and a ceramic bowl from a neighborhood garage sale. Friends who came for sleepovers had no idea what they were in for. I would get a thought in my head about where I wanted my bed to go or I’d become fixated on gluing something to the ceiling, and we’d get to work—sometimes for hours.

I couldn’t leave that bedroom alone. I reorganized. I reinterpreted. I reframed. I had three bookshelves and my idea of a really good time was to remove all the dust covers from my books, then put them back on, just to see how they looked. Even more thrilling, my bedroom connected to the small storage room where my stepfather kept his tools. I’d get an idea, like, maybe, hanging a canopy over my bed, and before you could say “popcorn ceiling,” I’d be up on a stepladder with a sheet, a staple gun, and a pocketful of thumbtacks. The vast majority of my teen years was spent trying to make that sheet hang from the ceiling, all the while thinking, There’s got to be a way to do this. Just as I would do sixteen years later on The Oprah Winfrey Show, I’d prepare my own “reveal” moments, dragging my barely patient mother into the basement and flinging open the door to show how new and improved the place looked with the bed in this corner and the bookshelves in that corner. Sometimes she was kind enough to shriek, “Oh my God!” but as a designer, she also had the wherewithal to call a spade a spade and say, “That doesn’t work for me at all.”

Does this sound a little odd to you? I guess maybe it was. But back in the early 1980s, I didn’t know anybody who wasn’t kind of quirky. Wham! and The Cure were in. So was androgyny and eyeliner. Our city was the mall, transportation was a skateboard plastered in neon stickers, the accessories of choice were fluorescent rubber bracelets worn a dozen at a time. My friend Ronnie was obsessed with collecting watches. Another friend lived for GUESS jeans and carving his hair into a mohawk. Some turned Synchronicity T-shirts into their daily uniform, while others devoted their every waking moment to following the Minnesota Vikings pre-season. My obsession was that 14 × 14 room in our basement—the one part of my life that could actually look the way I decided it should look, the one place that could change and grow and reveal and conceal, according to my mood. It was where I could most be myself as I attempted to figure out who exactly that was. And though I couldn’t have put it into words at the age of 13, playing around with stuff and receiving a concrete visual reward at the end is a big part of what design has always been for me.

THE STUFF I LOVED PLAYING WITH THEN IS THE STUFF I STILL LOVE TO PLAY WITH.

The stuff I loved playing with then is the stuff I still love to play with, and it came from prowling flea markets and yard sales and auctions and antique shops in the little communities surrounding my hometown. My mother watched me save my allowance and spend it on the things that mattered to me, listening to me say over and over again, “I really want that for my room,” as I stood there waiting for the person in the antiques place to return with the key that opened the cabinet that held whatever treasure I was lusting after. What can I say? I’m a sucker for the hunt, that eureka moment when you find something amazing at a good price that can potentially transform the entire spirit of a room. The more overstuffed and overloaded and junky and trinket-filled a shop was, the more my heart started pounding, and that feeling hasn’t quit or grown old since 7th grade.

My design (and real-life) world expanded when I turned 17 and my parents sent me to boarding school in Massachusetts. They were worried I was heading down the wrong path, and thought that a change of scenery might be useful. Like many small communities, our suburb could be neatly divided into two parts, with the upper-middle-class Jewish families on one side, and the bowling alleys and fast food chains on the other. I frequently gravitated to the other side of town, which was a fantastic breeding ground for antiques stores and pawnshops.

Cushing Academy, Ashburnham, Massachusetts, 1990 (Illustration Credit 1.7)

Most of my friends got cars when they turned 16 and used those cars to go to parties where we’d drink beer and listen to music turned up way too loud and smoke pot. It was the ’80s and it was the suburbs and there really wasn’t much else to do. But it turns out that you can spend only so much time watching your buddy wash his Mustang before you start feeling like you’re trapped in a John Hughes movie. The truth is, I was bored out of my mind.

I was also in debt. The department store where I worked after school gave me a store credit card, but neglected to give me a lecture on restraint, so like any 9th grader worth his salt, I immediately began charging everything credit could buy, which included a big chunk of the men’s department. On top of that, I was using my stepfather’s gas card not just to fill up my own car, but the cars of all my friends. Unleaded gas, on the house! “Why does Nate have to have that fancy watch?” my stepfather would ask. “Why does he have to wear those expensive shoes?” He thought my value system was way out of whack, and you know something? He was absolutely right.

Boarding school may be considered home-away-from-home-for-the-maladjusted in some circles, but I genuinely loved the entire experience. Plus, my mother’s family was from the East Coast, and being at Cushing Academy gave me a chance to explore that part of the world. At first I didn’t get it. Why did everyone dress in such an expensively sloppy way? Why did the school make us wear a coat and tie for dinner one d

ay a week? What was the architecture all about? How come nothing looked shiny and new? Why did my cousins, who lived in a leafy suburb outside of Boston, have those old plates out on display? What was with all the needlepoint pillows and the American antiques? And the real question: What was wrong with me that I showed up on campus with gel in my hair, only to be greeted by a student body outfitted head-to-toe in L.L. Bean? Within a week, you couldn’t tell me apart from them. (I still think of that time as my Duck Shoe period.)

At Cushing I fell in love with New England. My favorite times were Fall Free weekends, when I visited classmates who lived in Boston and Cambridge and New York City. And I began my fascination with France, thanks to my glamorous French teacher, Sheryl Storm, who had cool earrings, wore her bangs at a very chic angle, and rocked a designer scarf over her shoulder. Here we were, sitting in a classroom at the base of a mountain in western Massachusetts, but believing that we were in the heart of Paris. Ms. Storm made us feel what it would actually be like to wander into a French bakery and order a croissant and citron presse. There’s a word she taught us, debrouiller, which means “to manage” or “to get by.” She said that she didn’t want us merely to get by, she wanted to see us go to France and be able to “express our personalities.” Years later, I sent her a Louis Vuitton bag, with a note saying how much it reminded me of her, and she sent me back one of the most beautiful letters I’ve ever received.

Anyway, something about that sensibility must have stuck, because when I began going to Lake Forest College outside of Chicago, I remember an overpowering need for Ralph Lauren sheets on my dorm bed. My mother told me I was being ridiculous but I was so determined, I ended up scoring those sheets on sale at T.J. Maxx. I’ll go out on a limb here and venture a guess that I was one of the few freshmen who showed up for school with picture frames and decorative boxes in a hunt theme, too.

The Things That Matter

The Things That Matter